Science Alert

in case you feel like getting nerdy with me

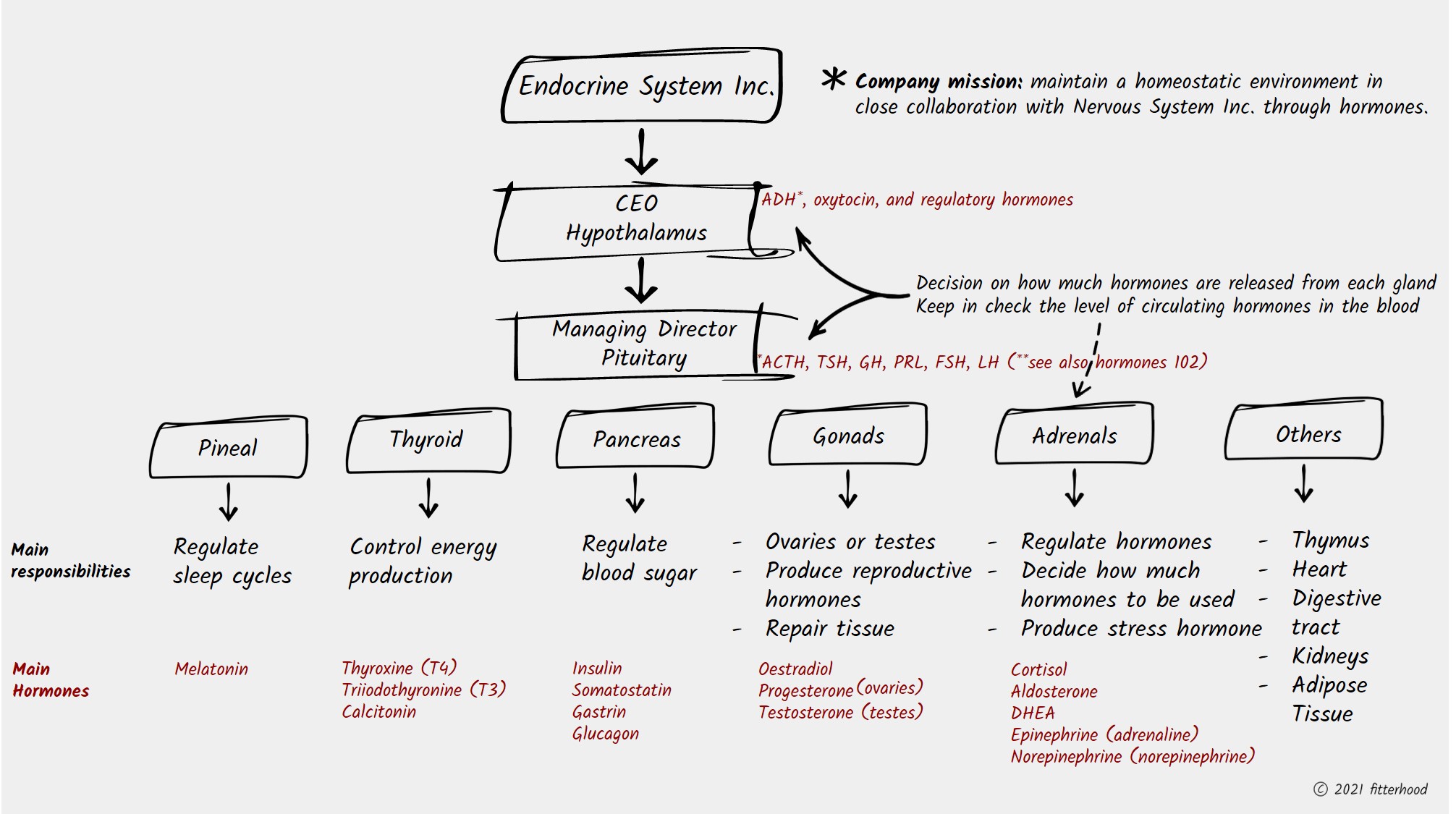

The endocrine system is a network of glands that release hormones to regulate the body’s organs and functions (mainly growth, development, mood, metabolism, immunity, and reproduction). Hormonal disruption can impair exercise results, with potential long term adverse consequences on health and wellbeing. Exercise also impacts hormones. Think of the endocrine system as a company with a CEO, a managing director, and first line managers with job descriptions and specific functions. There’s also teamwork and corporate politics.

Endocrine System Inc. has very complex dynamics. Hypothalamus is the CEO, and runs the show. He is the gatekeeper regulating the output of Pituitary.

With an office right next to Hypothalamus, Pituitary is the managing director who produces the major stimulating hormones, and leads first line managers, who in turn produce and communicate with the blood stream by releasing their hormones to do the work.

Now a closer look.

The mission of Endocrine System Inc. is to maintain a homeostatic environment in close collaboration with Nervous System Inc. (the mother company) through hormones circulating in the blood stream. A homeostatic environment is one where there is optimal functioning of the body’s organisms. A state of internal physiological and psychological balance, both physical and chemical, even when the external environment changes.

The various hormones produced by the Endocrine System do not work in isolation. They have interactive effects depending on their circulating concentration in the blood. They are key players in supporting health.

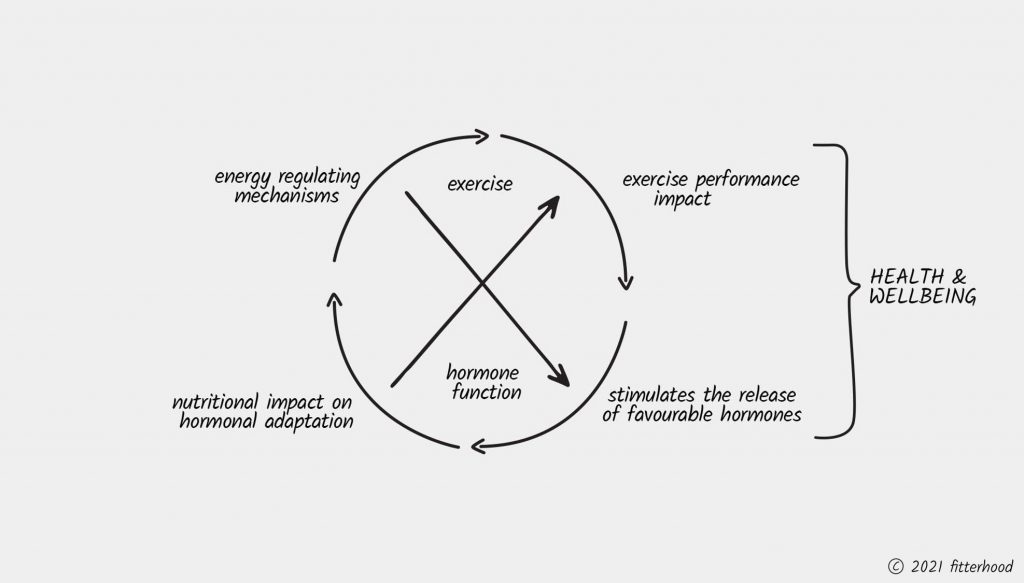

But what does the Endocrine System and hormone production have to do with exercise, performance, and wellness? More on that to come.

Bottom line: hormones affect exercise capacity, and exercise impacts endocrine rhythms – and they both influence optimal health and wellbeing on the path to wellness.

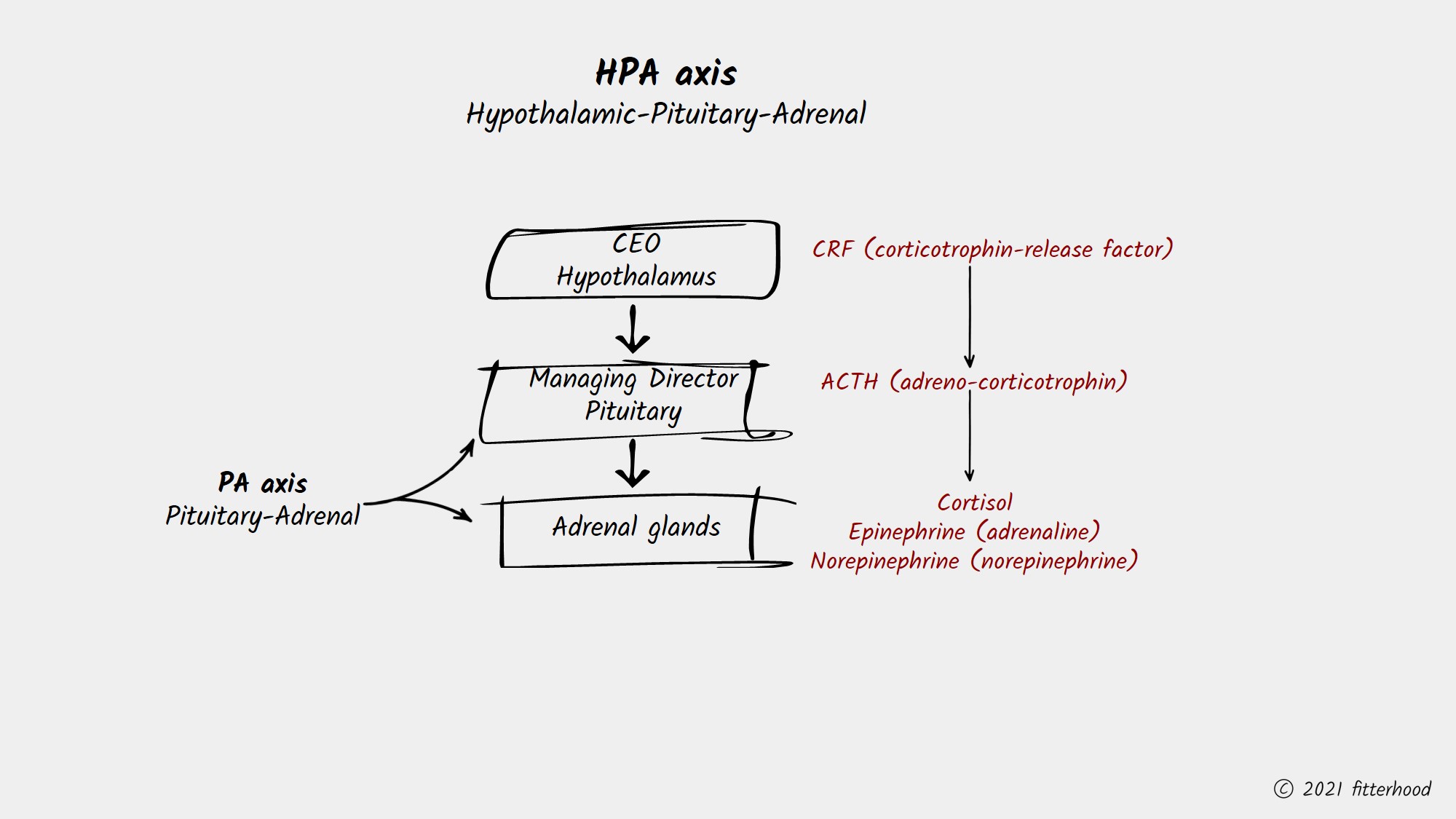

HPA axis and stress response

The HPA axis is composed of three inter-communicating neuroendocrine (Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal) central stress response system. The HPA controls the release of cortisol, the primary stress hormone, in response to environmental, physical and psychological stressors. Our body is designed with internal mechanisms which allow it to restore balance (homeostasis) and recover from natural stress responses.

Stress, both physical and psychological, will entail an increase in corticotrophin-release factor (CRF) from the hypothalamus. The CRF is a releasing hormone which stimulates the pituitary to synthesise adreno-corticotrophin (ACTH) hormone production. In turn, ACTH activates the production and release of cortisol from the adrenal glands. ACTH also increases the production of chemical compounds which trigger the increase of epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine (noradrenaline), the other two major stress hormones after cortisol. High cortisol levels in the blood stream will start to slow down the release of ACTH in a negative loop the restore hormonal balance. However, excessive and continuously high levels of cortisol due to chronic stress, can lead to a disruption in the normal HPA axis release patterns resulting from constant demand for neuroendocrine response due to prolonged stress.

Once this imbalance is in place, it can lead to many issues, one of them affecting the thyroid function. Excess cortisol has a diminishing effect on the conversion of thyroid hormone from its original inactive form (T4) to its active form (T3). In the same way, low cortisol levels can also impede T4-T3 conversion. The result is a low thyroid function and a low metabolism situation, both leading to weight gain.

Bottom line: optimal cortisol levels facilitate optimal thyroid gland function and thyroid hormone production and conversion.

Coming up: more on the role of cortisol and insulin.